Kyoden and Tsutaju were the bestselling Edo authors. Kyokutei Bakin became a merchant despite being from a samurai family.

Kyokutei Bakin was a representative playwright and yomihon author of the late Edo period. His real name was Takizawa Okikuni.

He was born in 1767 (Meiwa 4) at the residence of Matsudaira Nobunari, a samurai in Fukagawa, Edo, as the fifth son of Takizawa Unbei Okigi, a servant of the same family, and his wife Kado.

Bakin was familiar with illustrated books and other literary arts from an early age, and is said to have composed hokku at the age of seven. In 1775 (Anei 4) when Bakin was nine years old, his father died, and his eldest brother Okimune inherited the family business at the age of 17. However, for financial reasons, Okimune handed it over to the ten-year-old Bakin, left the Matsudaira family, and served the Toda family. His mother and sister also moved to the Toda family with Okimune, so Bakin was left alone in the Matsudaira family.

He loved reading from an early age, and was well versed in Chinese classics, Confucianism, Buddhism, and Japanese classics. After serving as a servant at a young age, he decided to pursue a career in playwriting.

[The master-disciple relationship with Santo Kyoden and working at Koshodo]

Bakin admired Santo Kyoden (1766-1781) and became his pupil. However, Kyoden declined to become his pupil, so he treated him as a friend. Bakin’s autobiography often mentions Kyoden, and it seems that Kyoden was both a teacher and a benefactor to him.

It seems that Kyoden’s introduction led to him working for Tsutaya Juzaburo of the Koshodo bookstore.

He is said to have started working as a live-in employee around 1790.

At Koshodo, he learned how to proofread books, transcribe manuscripts, and do all aspects of publishing work. According to Bakin’s records, he was promoted to clerk a year later in 1791, which shows how talented he was.

His experience at Koshodo was a valuable training period in which he not only mastered the practical aspects of publishing, but also interacted with comic writers such as Kyoden, Koikawa Harumachi, and Jippensha Ikku, and learned directly about Tsutaya’s publishing policies.

Tsutaya Jusaburo was the most influential publisher at the time, and Bakin, who grew up under his tutelage, built a solid foundation in the world of comic writing.

[Turning point to become a comic writer]

In the fifth year of the Kansei era, he married Momo (30 years old), the widow of the Aida family who ran the footwear store “Iseya” under Yotsugi Inari (now Tsukudo Shrine). At this time, he quit his apprenticeship at Koshodo, but it was Tsutajyu and Kyoden who encouraged him to marry her.

However, after about two years, he left the footwear store to become a full-time comic writer. In addition to a stable income, he also began to receive calligraphy fees, thanks to the arrangements of Tsutajyu and Kyoden.

Bakin’s first work as an independent writer under Tsutajyu was “Takao Funejimon” in the eighth year of the Kansei era (1796). The illustration of the courtesan Takao and a giant carp was by Eishosai Choki. It was the pinnacle of the sharebon that Kyoden had created earlier. It is a work that feels like an homage to the famous illustrations in “Kyosei Kai 48 Te.”

After Tsutaya Juzaburo passed away, Bakin sought new outlets outside of Koshodo and signed contracts with other publishers, expanding his field of work to include long reader novels.

Representative works (title/year of publication/publisher)

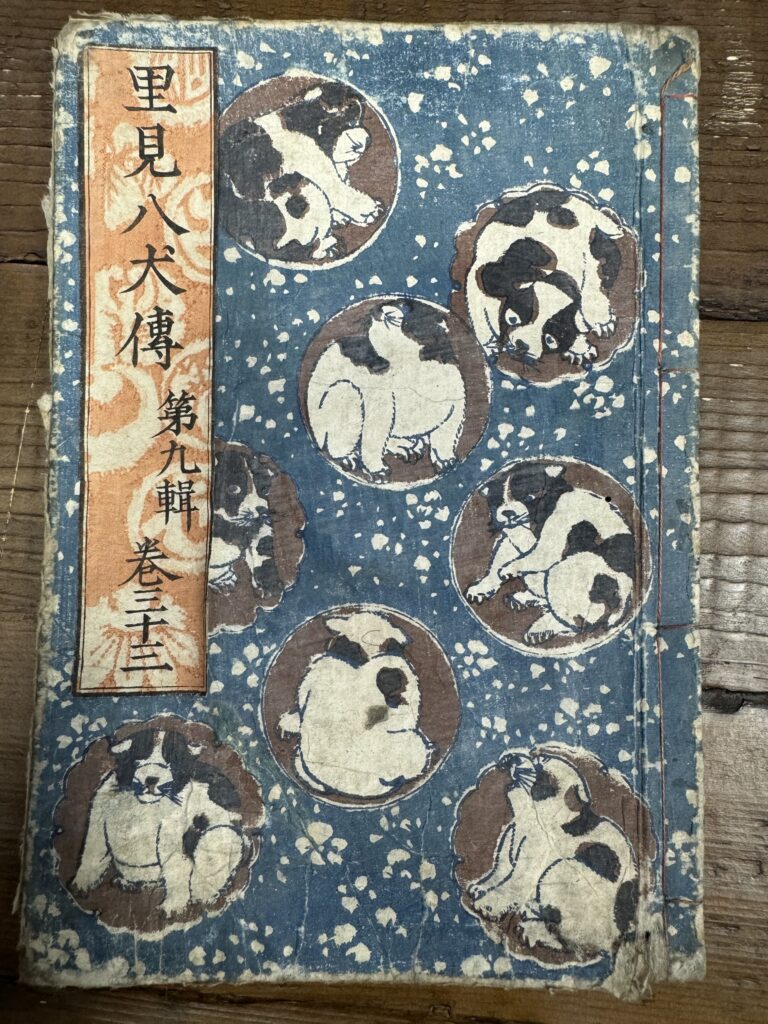

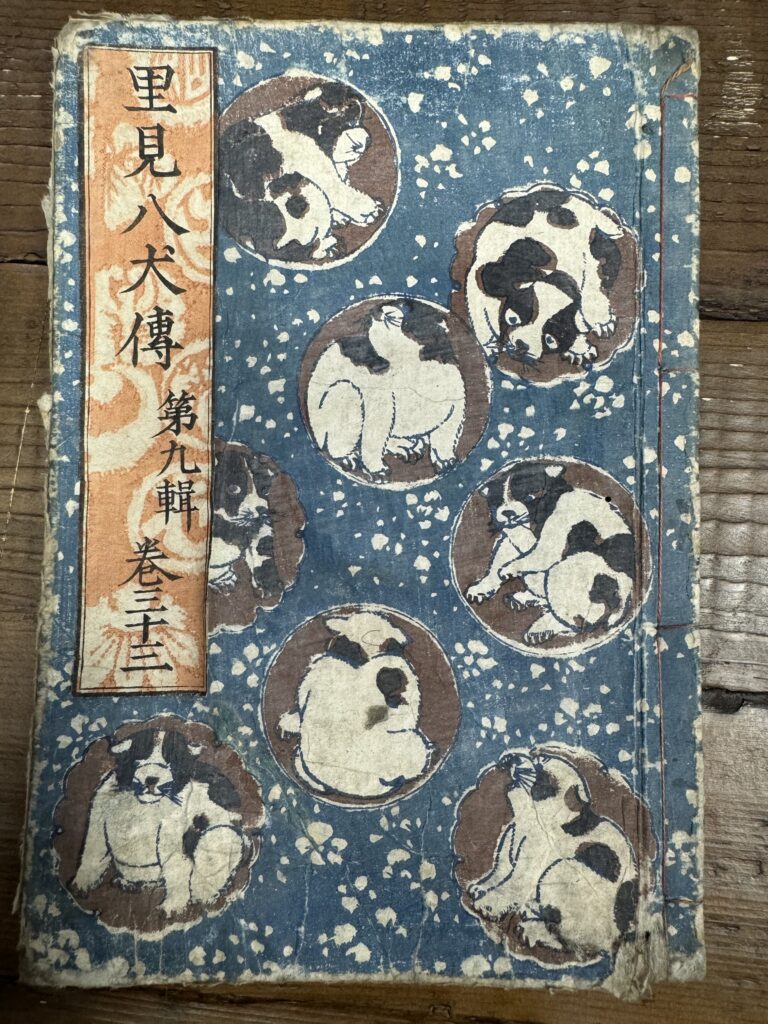

- The Legend of the Eight Dogs of Nansō Satomi

- Publication: 1814–1842

- Publisher: Kiemon Tsuruya and others

- This is the culmination of Bakin’s masterpiece, which rewards good and punishes evil.

- Camellia Theory Yumihari Moon

- Publication:1807–1811

- Publisher:Suharaya Ihachi

- The heroic tale of Minamoto no Tametomo.

- Blue Toji Flowers, Red Painting

- Publication:1812–1814

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- A story about thieves based on the character Nezumi Kozo.

- The Beauty Suikoden

- Publication:1805

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- A story about a courtesan adapted from the Suikoden.

- Nichirenki

- Publication:1816

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- A biographical reader of Nichiren Shonin.

- Parakeet Chuuki

- Publication:1805

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- A moral lesson in loyalty and karma.

- Kyounan Rubetsushi

- Publication:1809

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- A humorous comedy depicting townspeople’s society.

- Genji of the countryside

- Publication:1829–1842

- Publisher:Suharaya Ihachi

- An adaptation of The Tale of Genji.

- Sayo Shigure Sleeve Diary

- Publication:1804

- Publisher:Second generation Tsutaya Juzaburo (Koshodo)

- A reader depicting samurai society.

- Body doll body mechanism

- Publication:1804

- Publisher:Second generation Tsutaya Juzaburo (Koshodo)

- A comic work that deals with monsters and dolls.

- Asahi’s Aftermath

- Publication:1813

- Publisher:Kiemon Tsuruya

- Sengoku military chronicle.

Summary

Bakin learned to write comic stories from Santo Kyoden, and through Kyoden’s introduction he joined Koshodo as a live-in apprentice, where he was so highly regarded that he was made an apprentice after just one year. His time at Koshodo formed the foundation for the vast world of stories he would later build. He continued to work with Koshodo after the death of the first Tsutaju, perhaps as a way of repaying his debt to the second Tsutaju (Yusuke).

His achievements, which saw him reach the pinnacle of Edo culture through a wide range of genres, from comic stories to readings, still shine brightly to this day.

Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (a huge work consisting of 98 volumes and 106 books. It became a huge bestseller in the Edo period)

Torso Doll Limbs and Body Machine (a masterpiece with a yellow cover created with Tsutaya Juzaburo II)

Source: All books in the collection of Ukiyo-e Cafe Tsutaju