Incredible trivia

What is “oraimono” in Episode 17?

Why did Tsutajyo want to sell oraimono?

Episode 17 of the taiga drama “Berabou” sees the story moving toward the middle.

Due to resistance from publishers in the city, Tsutajyo was finding it difficult to sell Hosomi outside of Yoshiwara. So, he decided to sell educational materials called “oraimono” to the provinces.

Oraimono were teaching materials used at terakoya (temple schools), which supported learning in Japan for 900 years before the establishment of modern elementary schools. During the peaceful Edo period, education greatly influenced career advancement.

As a way to simultaneously develop sales channels and attract buyers, he asked influential people to help with editing. However, once the book was completed, the influential people involved in editing it knew how to buy it themselves for the sake of showing off. This scene shows Tsutajyo’s scheming side. From his works, we can imagine that the real Tsutaju was a manager who was more solid and meticulous in his planning than his flashy side.

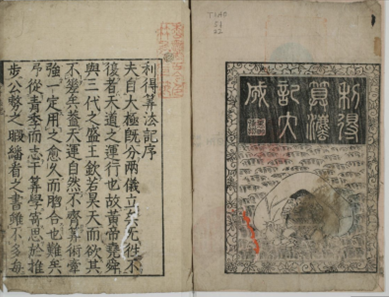

We also speculate that the reason Tsutaju dealt in oraimono was because they could expect stable sales every year. During the Kansei era, it is said that there were around 10,000 terakoya schools across the country. New students were admitted to terakoya every year. During the Edo period, not only samurai but also merchants and farmers studied at terakoya schools from the age of 6 to around 17, with desks lined up. Every year, new students purchased or borrowed oraimono. Even though the number of copies printed was small, this likely resulted in stable sales. Since sales could be made from a single board for a long period of time, sales for the following year could be predicted. What’s more, they could be sold not only in urban areas but also in rural areas. Oraimono are said to have originated as collections of sample letters for the exchange of letters. They covered a wide range of content, including how to read and write kanji, arithmetic, geography, and history. Famous authors included Takai Ranzan and Jippensha Ikku. The representative “Teikin Orai” (Teikin Orai) is a compilation of etiquette and letter-writing rules for samurai society, and was widely popular during the Edo period. Furthermore, Japanese mathematics, as exemplified by Yoshida Mitsuyoshi’s “Jinkoki,” describes highly advanced arithmetic even by global standards, and an efficient mathematical system using the abacus spread to the provinces. The historical drama “Berabou” introduced the “Kousaku Orai” (for farmers) and the “Daiei Shobai Orai” (for merchants). The Ukiyo-e Cafe is currently exhibiting two original Edo period works, “Teishin Sanpoki” and “Onna Imagawa Enkobai,” two representative correspondence works created by Tsutaya Juzaburo.

Profit Calculation Method, Koshodo Edition, 1788, Tenmei 8, compiled by Saito Takarin

Onna Imagawa Tsuya Koubai (Female Imagawa Tsuya Koubai), Tenmei 1, Koshodo Print

Reference Books, National Book Database