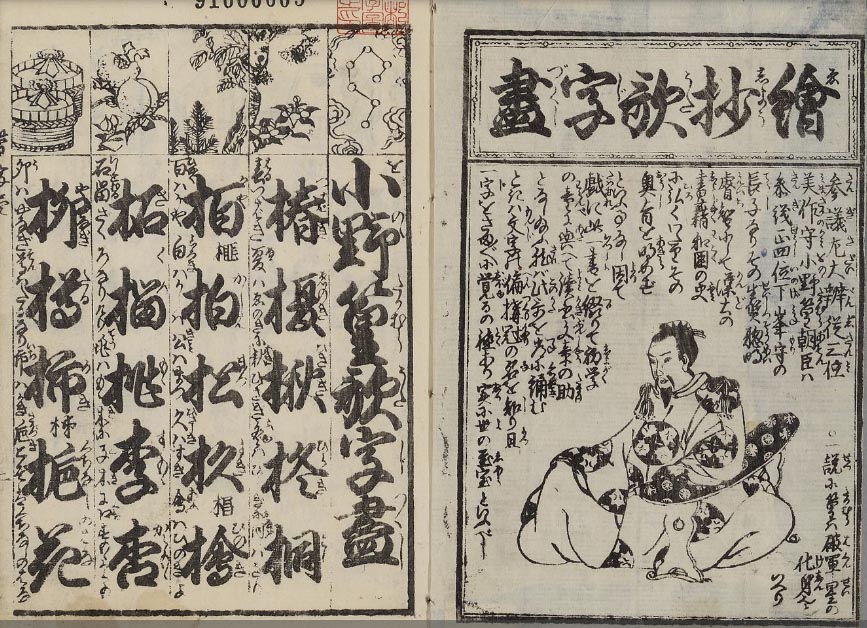

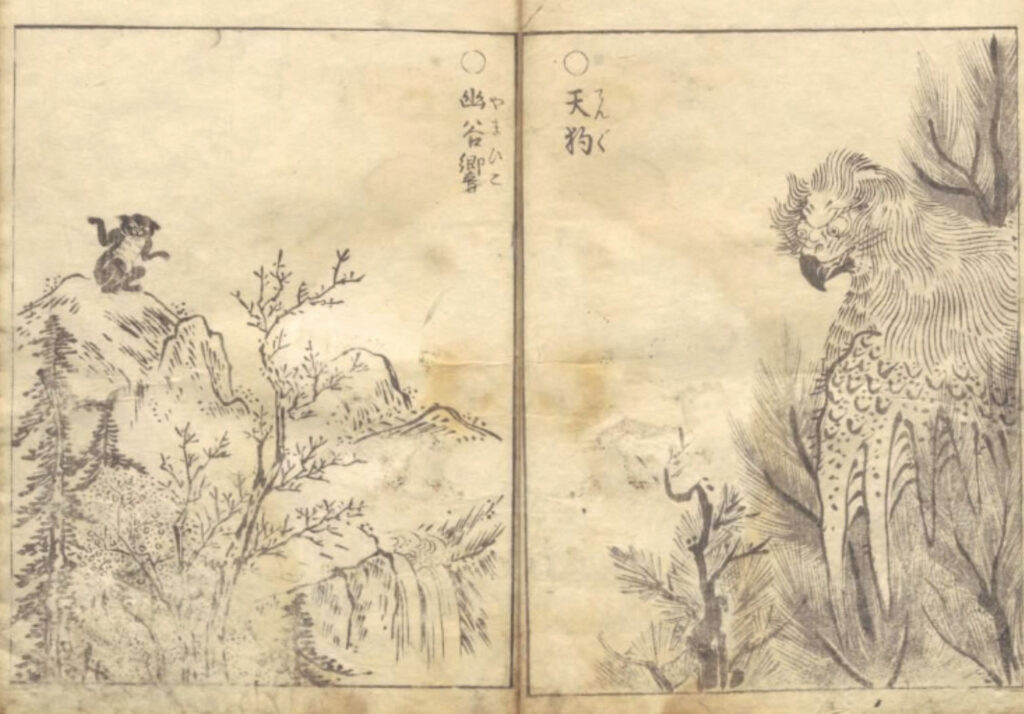

Image: Yoshiwara Keisei: New Beauty Collected Handwritten Mirror

Source: ColBase

Amazing performance by Kazuki Enari. Ito Atsushi plays the second generation Ichibei Daimonji, and his character is a brilliant performance!

Enari brilliantly portrayed the bold and arrogant lord of the Matsumae domain. It was scary. Ito Atsushi reprised his role as the second Daimonji Ichibei, adopted after the death of the first Daimonji Bunro. He played a more feminine character, a stark contrast to the first, and even Ito’s appearance is instantly recognizable. It’s scary to think that the devilish “Daresode,” the eye of the storm, will gradually come into her own as the second Daimonjiya courtesan.

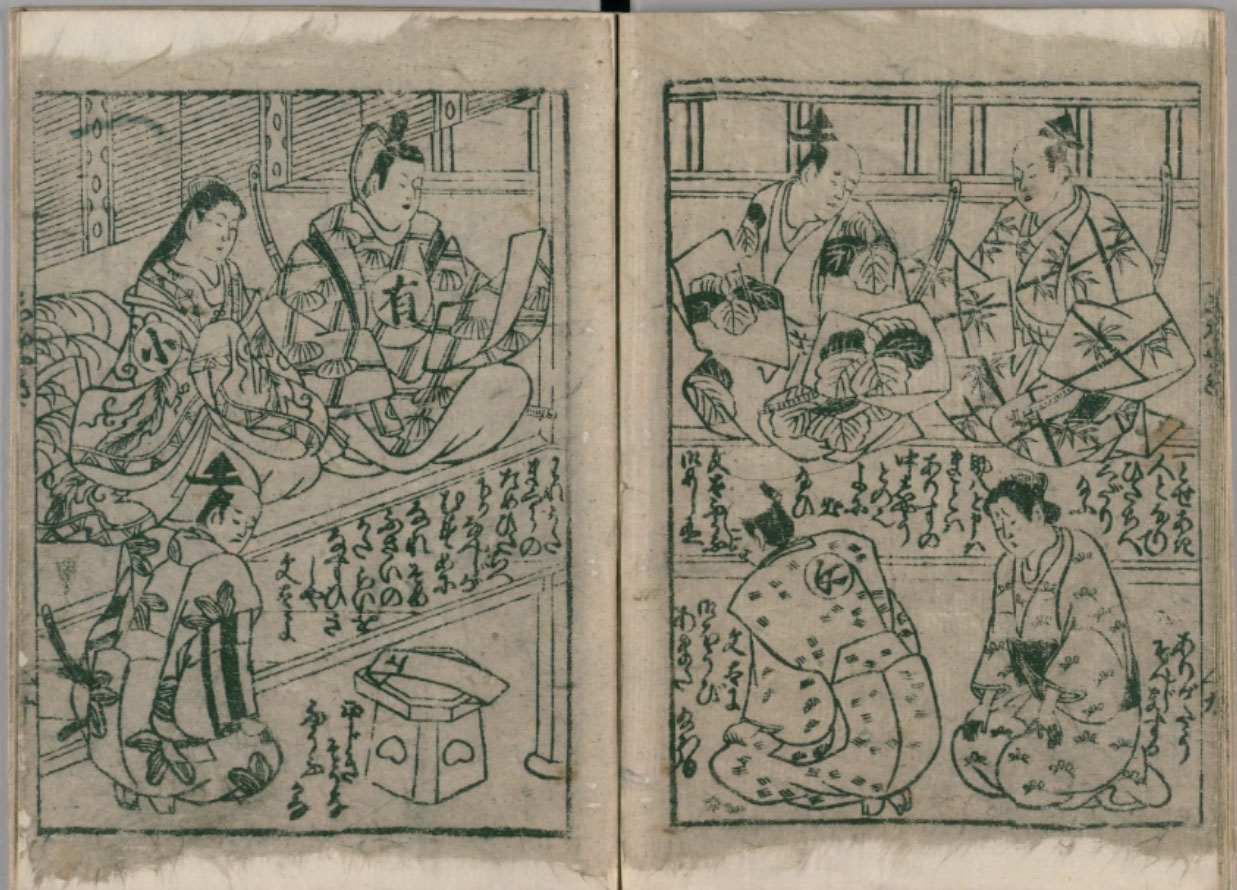

Tsutaju had been steadily rising in the taiga drama “Berabou,” but in episode 21, she suffered a major setback. In the previous episode, she plagiarized Nishimuraya’s “Hinakata Wakaba Hatsumoyo,” but her published work, “Hinakata Wakaba Hatsumoyo,” didn’t sell at all. The reason for this was “instructions.” Instructions are instructions a printer receives from an artist or publisher when printing a work. He gives instructions on a variety of things, such as color placement, intensity, printing position, and paper size, and these instructions can significantly affect the final quality of the print. In short, while Utamaro’s skilled impersonation allowed him to create a rough sketch that rivaled the original, Tsutaju’s inadequate instructions resulted in poor color development and ultimately a print that fell short of Nishimuraya’s Nishiki-e. This is true in modern society, too. Take generative AI, for example. While generative AI can produce creative works, the quality of the finished product depends on whether you can give specific, accurate instructions about what you want it to create.

Experience is important to be able to give such specific, accurate instructions, and Tsutaju lacked that experience. I recently had a similar experience. At Ukiyo-e Cafe Tsutaju, we’re taking on a new challenge: becoming the publisher ourselves and reviving Tsutaya Juzaburo’s masterpieces. During the woodblock print production process, we often encounter situations where we have to give instructions to the publisher, carvers, and printers. I realized that producing reproduction woodblock prints requires comprehensive knowledge and experience of processes, techniques, materials, and historical context, and that good communication with the artisans is also paramount. Without clear instructions from the publisher, the intended work cannot be completed. In this drama, it seems that Tsutaju lacked both experience and knowledge. As Nishimuraya says, multi-colored nishiki-e prints cannot be produced overnight with superficial knowledge!

Then, in episode 21, an incident occurs that further depresses Tsutaju.

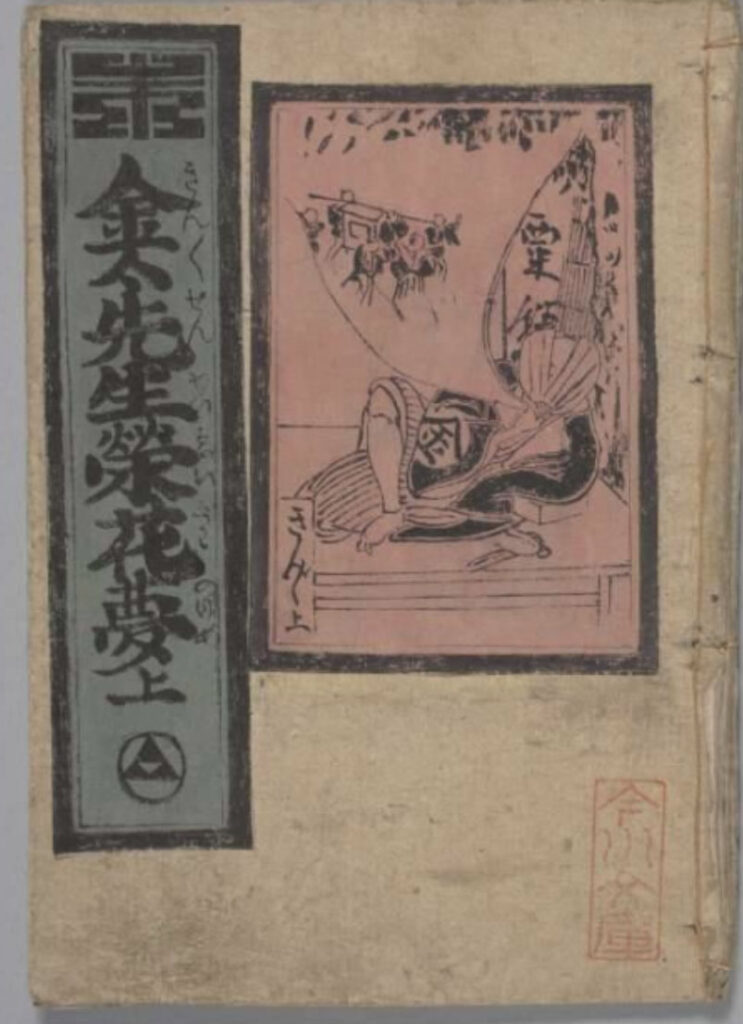

The cause of this was my favorite, Sankyoden (Kitao Masaen). Masaen published a blue book under the name Sankyoden through Tsuruya. Until then, Tsutaju had had a close relationship with Kitao Masaen as an artist, but had not recognized Masaen’s talent as a playwright. That talent was discovered by Tsuruya, a rival shop with a long history with Tsutaju. Thanks to this, Santo Kyoden made great strides. Tsutajyo, keenly aware of her own lack of ability and losing confidence, was encouraged by Ota Nanpo, who said, “Your lack of experience is your strength.” With these words, “That’s why you can produce things that people who have been doing it for a long time can’t,” Tsutajyo reaffirmed that her strength lies in her planning ability.

In the near future, Tsutajyo will overcome this setback and form a golden duo with Santo Kyoden, completing “Yoshiwara Keisei: New Beauty Collected by Hand.” It seems like this episode will be a little further down the line.

From there, she starts coming up with ideas one after another, and together with Santo Kyoden, they produce a string of hits with their yellow-covered books and sharebon books. It’s something to look forward to in the drama going forward.

Another highlight of this episode was the impressive acting of the actors. There were plenty of highlights, including the eccentric performance of Enari Kazuki, who played Matsumae Michihiro, the lord of the Matsumae domain, the alluring performance of Fukuhara Haruka, who played the courtesan Daresode, and the stark contrast between the character played by Ito Atsushi, who returned as the second-generation head of Oomonjiya, also known as "the pumpkin husband," who died in the previous episode. I'm looking forward to future developments!